About Me

I am a Lecturer in Comparative Literature at Binghamton University, State University of New York. At Binghamton, I teach World Literature I and II as well as courses in medieval and early modern studies.

My research spans the theater of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, gender studies, reception and adaptation studies, and history of the book. My writing has appeared in a variety of academic and public venues. I have recently completed a new introduction to Much Ado About Nothing for the Oxford World's Classics editions of Shakespeare and am working on a book manuscript entitled Getting Even: Gender, Genre, and the Revenge Plot in Early Modern Drama.

Before coming to Binghamton, I was a Perkins-Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in the Princeton Society of Fellows. I hold a Ph.D. from Harvard University, master's degrees from Harvard and the University of Oxford, and a B.A. from Duke University.

Selected Publications

“Rhodes’s ‘Fair Example’: Race, Tyranny, and the Orient in The Maid’s Tragedy”

This essay argues that the setting of Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Maid’s Tragedy (1610) on Rhodes is significant for the play’s representation of tyranny. In it the royal mistress, Evadne, kills her lover in an act the new monarch deems “a fair example” for “lustful kings” (5.3.292–93). The essay’s first section demonstrates that via Rhodes—Ottoman territory since 1522—the play affiliates “lustful kings” with proto-Orientalist textual and performance traditions, linking despotism and decadence. Parallels with Kyd’s Soliman and Perseda (1592) support this claim. The second section identifies a symbolic expression of the play’s racial geography in Evadne’s wedding masque (1.2). Styling the King as an overly bright sun blackening Night (i.e. Evadne), the masque parodies Jonson’s Masque of Blackness (1605) to render tyranny’s effects as a somatic mark. Dramatizing the racialization of religion, the masque manifests the intemperate sexuality that proto-Orientalism associated with Islam as darkened skin. The third section argues that when Melantius convinces the once “fair” Evadne that the King’s lust has made her “foul,” thereby spurring her to revenge, the play presents a scene of conversion. In this way, by killing the king—and ridding Rhodes of tyranny—Evadne washes herself and the island white.

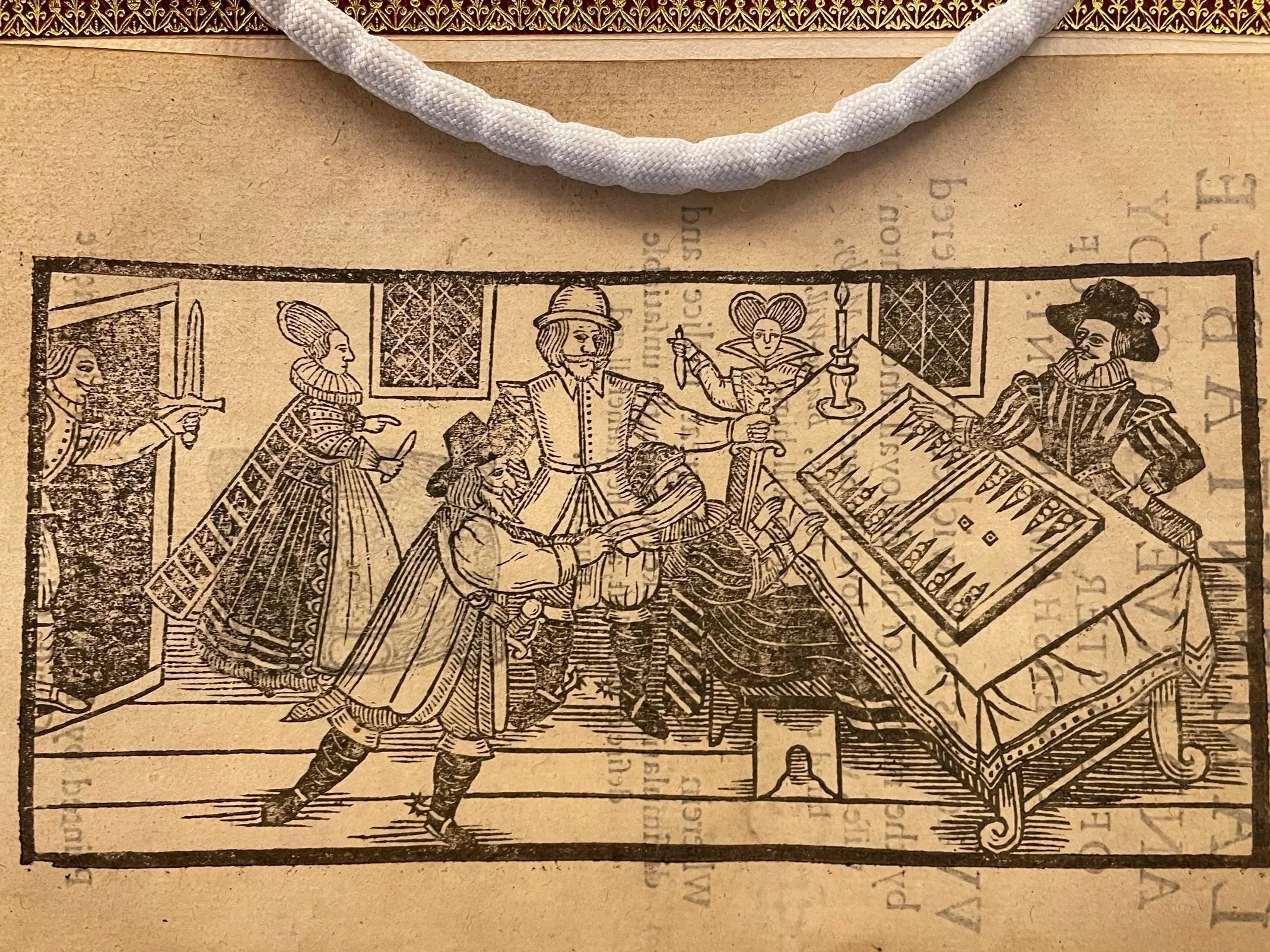

“The Sexual Politics of Paratexts: John Day’s Gorboduc”

Because Gorboduc, or The Tragedie of Ferrex and Porrex (1561) sees a king divide his kingdom between his two sons while he still lives, much scholarship discusses the play as an Elizabeth succession parable. However, the printer John Day’s prefatory letter to his 1570 octavo (O2) provides a different frame, documenting an instance of Gorboduc’s later reception that scholarship has not yet recognized. This article argues that by comparing the playtext to a sexually assaulted woman Day does not merely advertise his edition’s supposed superiority to O1, as some have claimed. Considering Day’s reformist network, his investment in preserving Protestantism in England, and his output in 1570—including the massive second edition of Foxe’s Actes and Monuments and political treatises by Gorboduc’s co-author Thomas Norton—Day’s ‘better forme’ of Gorboduc becomes newly legible within histories of reading. For by claiming O2 will ‘play Lucreces part’, Day reads Gorboduc’s materialization of misrule’s effects through violence against ‘Mother Brittaine’ as anti-tyranny polemic—and asks book buyers to read it this way as well. Synthesizing historicist and feminist literary approaches with recent book historical work on paratexts, this article demonstrates how O2’s prefatory letter figures gender violence to justify resistance to tyranny.

The Winter’s Tale and Revenge Tragedy

Vendettas, poisonings, madmen, ghosts––these tropes undeniably locate The Winter’s Tale in the revenge tragedy tradition. Yet Leontes’ spurious accusations and Paulina’s redemptive retribution double and subvert such generic markers, culminating in not a tragic but a comic end. This article reconsiders the genre of The Winter’s Tale’s through an intertextual and intertheatrical lens, revealing indebtedness to early revenge tragedies by Kyd, Marston, Chettle, and Middleton. The essay argues that Shakespeare structures Acts 1–3 of The Winter’s Tale around revenge tragedy tropes (madness, poison, ghosts, and the language of moral accounting) while deliberately unsettling their conventional logic. In Act 5, Paulina redirects the tropes of revenge tragedy toward reconciliation, particularly by performing Hermione’s ghost (“Remember mine!”). Shared material with The Second Maiden’s Tragedy, attributed to Middleton and (like Shakespeare’s play) performed by The King’s Men in 1611, takes on new significance, establishing revenge tragedy as constitutive of this play’s hybrid genre. This article then argues that, for its first audiences, The Winter’s Tale depended on a pervasive aura of metatheater, an awareness of an incipient “revenge comedy.”